A Nigerian public hospital treating patients with dignity and respect? That must be a contradiction in terms. But it is a true life story.

In January, an undercover investigation by TheCable had exposed the rot at the Federal Neuropsychiatric Hospital, Yaba, Lagos. The undercover reporter spent 10 days on admission in the hospital tracking corruption — after going in pretending to be a drug addict requiring rehabilitation.

While the anomalies uncovered at the Federal Neuropsychiatric Hospital were still generating reactions, a patient called the attention of TheCable to the Federal Medical Centre (FMC), Ebute Metta. Unlike “Yaba Left” where there were poor service delivery, arbitrary charges and mal-treatment of patients, the comments on this particular government hospital were glowing. TheCable decided to visit the facility undercover.

Tucked in the belly of the vast land housing the Nigerian Railway Corporation in Ebute Metta, the hospital captures the imagery of a utopia in a desert. Formerly the Nigerian Railway Hospital, the facility was inaugurated in November 1964 by the late Nnamdi Azikiwe, then president of Nigeria, to cater to the needs of workers and members of the once-booming corporation. In 2004, the hospital was commercialised and upgraded to a Federal Medical Centre (FMC).

NO DELAY IN GETTING MEDICAL ATTENTION

As early as 11am in the morning, the general out-patient clinic (GOPC) was already crowded as this reporter joined other patients sitting under the canopy. One of the officials from the medical record department handed the short registration form to the new visitors. Within a few minutes, a middle-aged woman had inputted my data into the laptop and pointed me to the payment desk where I paid N1,250 for e-registration and consultation fee. A payment receipt was immediately generated through an electronic channel after which I was handed a card, like an ATM card.

“That’s your electronic card. It contains your record with the hospital. Bring anytime you are visiting,” an official instructed as he directed me to the waiting room to see the doctor.

Each official at the record department had a laptop. The young doctors too had on their tables. Shittu, one of the doctors, swiped my card with the reader as she confirmed my details and asked what the problem was. She smiled and interjected at intervals as I explained the nature of bacteria giving me nasal irritation. Then, she began to register my complaints in the computer as she referred me to the ear, nose and throat (ENT) specialists.

At the pharmacy, the officials asked for my e-card, swiped on the card reader to access information on the doctor’s prescription. There was no way I could see what was prescribed or possibly have access to it. I was only informed of the content and amount. The pharmacist directed me to the payment point where I presented the card again. From there, I moved to the billing point where the payment was ratified.

Back to the pharmacy, I presented the electronic bill and the drugs were dispatched. Aside the payment points coordinated by Remita, officials of the hospital did not ask for extra cash or further payment. All they asked for was the e-card which reflects the patients’ medical and financial history.

‘PAY CASH AT YOUR OWN RISK’

When I spoke to a nurse at the specialist clinic, she said paying money to any member of staff is at the patient’s risk as it will not reflect on his/her record online. “Only those at the payment point can collect any form of cash. It goes straight into your electronic account and any staff attending to you will see that you have paid for the service you have come for. Any other staff caught collecting money from patients will be penalised. So, they’ll rather refer you to the payment point,” she said.

I later learnt that the hospital introduced an electronic medical record (EMR) system in August 2019 to curb sharp practices among its officials. At the radiography department, Umonnam Uwem explained, with the patience of a skilled teacher, the function of the modern computed tomography (CT) scan using an onion as analogy. While she tabled one hand and straightened the other to form an imaginary knife cutting a fresh onion, the director proceeded to demonstrate how the massive doughnut-shaped machine, procured four months ago, scans the body in slices to produce a vivid cross-sectional imagery of what is happening inside.

Not until when the onion is properly sliced can you identify if parts of it is decaying even while it looks fresh on the outside, Uwem explained. From there, she moved to the mammography and illustrated how the procedures are captured in the computer system, including how they are digitally processed and sent to the central system.

Typical of most public health institutions in the country, FMC suffered years of neglect with regards to infrastructural decay. From leaking roofs, inadequate equipment, poor electricity supply and lack of transparency, corruption thrived aplenty.

‘STAFF USED TO PRINT THEIR RECEIPTS’

The process of sorting the wheat from the chaff began in 2017 when a new management came on board. In slicing through the “onions” to diagnose and treat the decomposing system, the management digitised its clinical and financial services. But the change did not come that easy.

“When we came in the payment mechanism was such that patients brought their money from their homes and handed over to our staff and so the issue of printing receipt was not unknown. People printed their receipts, give their receipts, collected the money,” Olorunfemi Ayoola, the hospital’s head of corporate communication, told this reporter in an interview.

“That and many other issues were prominent. In any case, the subsequent outcome when we stopped that has proven that it was extremely very prevalent because the very first month we stopped that, we had almost 100% increase. Fortunately for us, the federal government had started the TSA procedure that says that all money must go into the federal government’s account. The federal government itself had appointed an agent for that purpose. And that agent is Remita.

“So, what we did was to bring in Remita. Any payment that is going to be done in this institution should be done to you. So, what our staff just do is basically to confirm that the payment is in consonance with the service that is about to be rendered. If you have paid N10,000 for some drugs, call our staff to pay directly to Remita and it goes directly into our account and the MD can monitor it on his phone real time. He is not the only one who can monitor it. The accountant will monitor it and the auditors are monitoring it.

“You are coming into the hospital, you think you are going to spend a week and they have given you a bill, you can pay for instance, N100,000 into your wallet electronically and all you have to do is take your card to the service point and then pay. We deliberately made it such that you still need your ATM before we can debit you, so that you are also aware of the debiting process, so that there is no controversy.”

According to Ayoola, bringing the EMR system to improve the hospital’s financial base has not rendered the staff redundant, but it has only changed their roles. On the bidding process, he said the hospital has been very open and follows the public procurement process which has made it hard for anyone to bypass the established process.

“We also have POS, so if you don’t want to pay directly to Remita by cash, you can pay by POS. But as it is today, since the last two years or thereabouts, none of the staff has collected money from any patient. All that we have been able to do is to put in checks and balance to be sure that the government appointed agency is also very faithful to the system.”

NO MORE MANIPULATIONS

With about 55,000 patients and 1,200 staff on the EMR system, Abdujelil Toyinbo, the IT consultant, said the era of manipulations is gone as all wards and departments in the hospital are connected to the system.

“We can monitor the allocation of bed spaces and the flow of money every second. It has created transparency, accountability in the work flow,” Toyinbo said. Omolola Awe, a matron who heads the anti-corruption and transparency unit at the centre, said members of her team move round the wards and departments unannounced to observe inadequacies and report to the management. Hence, all staff are kept on their toes.

Lending credence to that, Adedamola Dada, the medical director, said reducing graft and creating efficiency in public institutions is all about entrenching a sustainable system.

“Basically, that is why I said that what we are building is a system. It is a culture. We are on a quality improvement programme of our system,” the MD said. “In fact, most public policies are targeted at creating a good system. And once you don’t have the intention of subverting it for personal gains, then there is no headache. For procurement law, when I came in, I insisted we must follow it and it worked. And we created a system for it to work. There is no public policy that is hampering my capacity to deliver.

“For me the biggest strength that I have here are my members of staff and they are also my biggest weaknesses. We keep doing the training, talking, appealing and for me that is the biggest challenge.”

PATIENTS ADAPTING TO THE DIGITAL PROCESS

According to Toriola Yusuff, one of the patients, the new initiative makes life very easy unlike the system where he moved about with a paper card from one ward to the other. For Yusuff, he accesses medical services after and spends fewer time at the clinic anytime he visits.

“This is my card too. I keep it beside my ATM card in the wallet in case I need to come here as a matter of urgency,” Yusuff said. “This is the kind of services I enjoy. I want it done fast with quality. Most importantly, it is affordable. It makes me trust the process more.”

According to Ayoola, the hospital welcomes about 5,000 visitors monthly. “We have done our study and we saw that half of the time patients spend in the hospital, they are sitting down while we search for their case notes. Some of those case notes have not been used in one year. We became the only hospitals in this country whose GOPC works till 8pm, all others close 3 to 4pm,” he said.

James Odofin, one of the doctors, said he could easily access patient’s medical history from his laptop or computer tab. “Patients can be reviewed at any time without the record officers coming around. Then, we can keep track of the last official who saw the patient, the date and time. It’s good for statistics. I’m now very careful in putting down things because anyone can see it and it cannot be deleted.”

PUBLIC PRIVATE PARTNERSHIP (PPP) INITIATIVE

Taking over a medical facility with little and outdated equipment at assumption of office, Dada said he realised that the centre could not raise the huge amount required to fix the overwhelming challenge of infrastructural decay. While the centre continues to procure more equipment, he initiated the PPP re-agent placement in September 2019 to bring in private sector investment. From the microbiology, haematology labs to the blood bank, the spaciously neat rooms are decorated with all sorts of heavy machines that run into millions of naira funded through the PPP. Patients no longer go outside to conduct tests. With the state-of-the-art facilities, it now takes less than five minutes. According to the MD, the mission is to reduce medical tourism abroad and give Nigerians quality service.

“It is effective in that it is able to bring in the critical resources that we need, so that the resources we have can be diverted to other areas that are not viable in terms of PPP,” Dada said.

“We can divert to areas of taking care of the indigents because our policy here is that we don’t reject patients. We treat first before we ask for money. For me, the aim is not profit to the hospital. The aim is service to the hospital.”

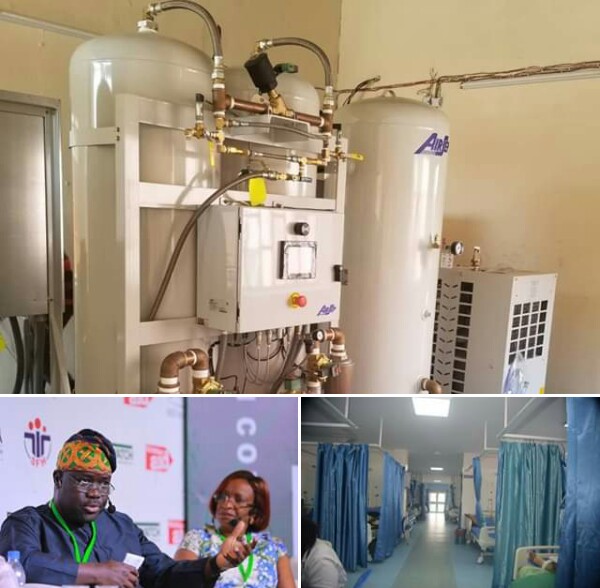

Few meters away from the dialysis centre stands the massive medical oxygen plant inaugurated early January. According to the operator, it produces a minimum of 60 cylinders of oxygen a day, meanwhile the centre only needs half of it. Based on this factor, the management began the process to commercialise the facility to help other hospitals meet their oxygen needs.

“A hospital collects 240 cylinders from us in one month,” the operator said.

Despite its small space, one of the most fascinating sights at the 210-bed centre is the private ward. As the electronic door opened, I was ushered into the well-paved ward where it is one patient to a room. For the platinum, the patient parts with N120,000, executive N90,000 and standard N70,000 – just for one week. Even in dire medical condition, the rich here bask in absolute comfort as the rooms are fitted with kitchenets and all sorts of extravagance.

But Dada said it doesn’t end there until the plans to bring artificial intelligence into the system within two years is achieved. And then to more complex procedures as endoscopic and keyhole surgeries.

“Every patient would have his own monitor from which data will be streamed to the nurse. And then we are going to have two new theatres and a central sterile services department (CSSD). Our target is to have the best CSSD,” he said on a final note.

Bidding the medical centre goodbye to face the blarring horns, I encountered the static traffic and smelly gutters of Ebute Metta with a nostalgic feeling for a reporter who had set out to observe the familiar narrative in the Nigerian public health system, but returns home with a story of hope.