No one contributed more to the building of America than the black man. By the works of their hands, labor, ingenuity, and suffering, Black people made America great.

Although the American and world educational system does little in recognizing these contributions, we take pride in teaching the scientific, architectural, and social achievements of men such as Benjamin Banneker.

In the Stevie Wonder song “Black Man,” the Motown star sings of Benjamin Banneker: “first clock to be made in America was created by a black man.”

Though the song is a fitting salute to a great inventor (and African Americans in general), it only touches on the genius of Benjamin Banneker and the many hats he wore – as a farmer, mathematician, astronomer, author, and land surveyor.

Like a lot of early inventors, Benjamin Banneker was primarily self-taught. The son of former slaves, Benjamin worked on the family tobacco farm and received some early education from a Quaker school. But most of his advanced knowledge came from reading, reading and more reading.

At 15 he took over the farm and invented an irrigation system to control water flow to the crops from nearby springs. As a result of Banneker’s innovation, the farm flourished – even during droughts.

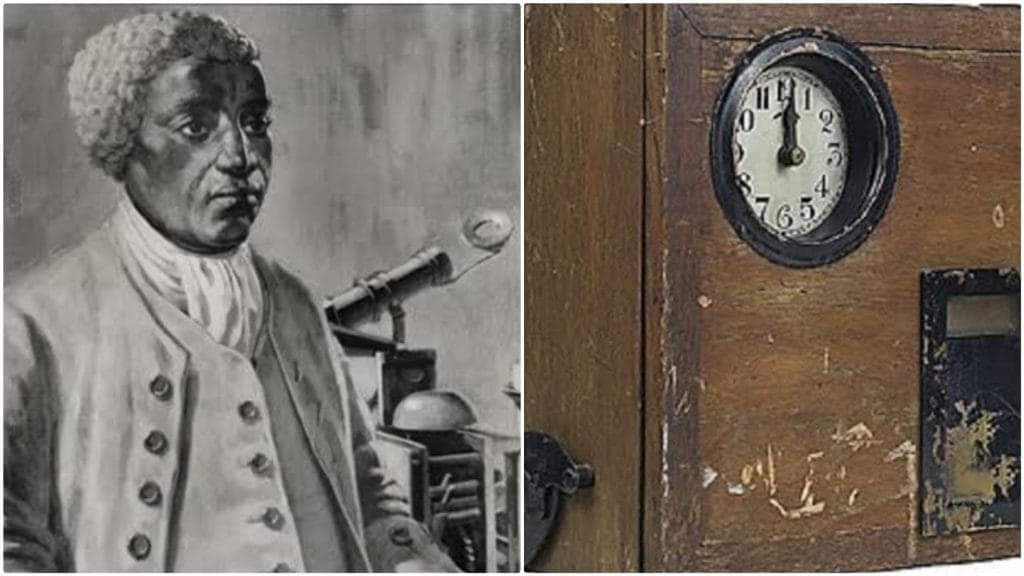

But it was his clock invention that really propelled the reputation of Benjamin Banneker. Sometime in the early 1750s, Benjamin borrowed a pocket watch from a wealthy acquaintance, took the watch apart and studied its components.

After returning the watch, he created a fully functioning clock entirely out of carved wooden pieces. The clock was amazingly precise and would keep on ticking for decades. As a result of the attention his self-made clock received, Banneker was able to start up his own watch and clock repair business.

Benjamin Banneker a Multi-Genius

Benjamin Banneker’s accomplishments didn’t end there. Borrowing books on astronomy and mathematics from a friend, Benjamin engorged himself in the subjects. Putting his new-found knowledge to use, Banneker accurately predicted a 1789 solar eclipse.

In the early 1790s, Benjamin Banneker added another job title to his resume – author. Benjamin Benjamin compiled and published his Almanac and Ephemeris of Pennsylvania, Delaware, and Maryland (he would publish the journal annually for over a decade), and even sent a copy to the secretary of state Thomas Jefferson along with a letter urging the abolition of slavery.

Impressed by his abilities, Jefferson recommended Benjamin Banneker to be a part of a surveying team to lay out Washington, D.C. Appointed to the three-man team by president George Washington, Benjamin Banneker wound up saving the project when the lead architect quit in a fury – taking all the plans with him.

Using his meticulous memory, Benjamin Banneker was able to recreate the plans. Wielding knowledge like a sword, Benjamin Banneker was many things – inventor, author, scientist, anti-slavery proponent – and, as a result, his legacy lives on to this day.

Conclusion

We will keep insisting and advocating for the total overhauling of the History classes that are being taught to African students both at home and abroad.

It is often disgraceful and painful when African adults open their mouths in wonderment when they stumble on these kinds of lessons in history. They are astonished because they were not taught as children.

We can only do our best to publish these facts here about our people. But more responsibility rests on the shoulders of our governments and schools to make the history and achievements of our ancestors important. It will help boost the pride and morale of our people to strive to do better.

-Triple A