“Now cracks a noble heart. Good night, sweet prince/ And flights of angels sing thee to thy rest.” – Shakespeare

After I researched and wrote his biography, anytime I saw Abiola Ajimobi it was not the politician, or governor or senator that leapt into my eye. It was the altar boy, crisp, smart, the sparkle of childhood. In his primary school, he was selected to that status, though a Muslim, by the school because he was spick and span. Face upended faith.

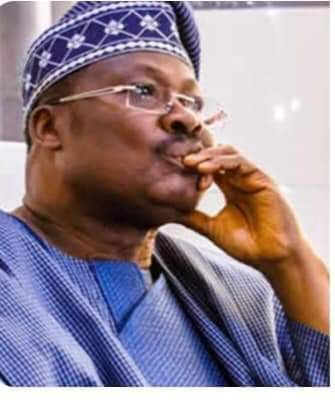

He was always the model student in hygiene and fashion. His shirts, his trousers, his shoes, body cream, haircut were examples for others. His daughter Abisola told me how he paid attention to his appearance. From his skin, his bath to his clothes for the day. He would spread a variety of apparels on the bed and meticulously make a judgment, sometimes consulting wife or any member of his family, on what to wear.

Even his colleagues at National Oil and Later Conoil described him as “dapper,” reminding one of the politician in Achebe’s A Man of the People who was described as “the best dressed gentleman.” In his corporate life, his suits blazed in cuts and colours. Even his wife Florence testified to her surprise about how he, as a politician, swiveled into the traditional Yoruba wear of agbada and sokoto with a tailor’s ease

If what the experts say is correct that we should follow the laws of hygiene in this era of COVID-19, the last person I expected to fall victim is Ajimobi. Yet, that virus that respects neither class nor faith nor courage struck, and fatally. In his play, Twelfth Night, Shakespeare’s Sir Toby noted, “Care is an enemy to life.” Care did not save one of the most careful men on earth. It is a nightmare of a paradox, a dark foreboding for all alive.

It is a lesson in human impotence. It is not a time to say with the superstitious folks that he died because he wished to say his farewell at 70. Now many will say his 70th birthday was his big, final valediction to the world. It was a fanfare of a party, the big and mighty in the nation came, so did the small in Ibadan. He, too, was in an ebullient spirit. He had a good dance with his wife, and spoke with great hope and rapture about his age and aging, and even his virility, when he quipped that the Ooni of Ife had assured him, kabiyesi so pe ara mi maa ma le. “His majesty said my body will be virile.”

And he was. He was agile, full of the gift of life and possibilities, and he earned his place again atop the political world. He died as acting chairman of his party. He had told me in his last days as governor that he was contemplating going back to school. During the lockdown before the flu struck, returned my phone call and assured me he would keep in touch over his new post as deputy chairman. But as Joseph Conrad says in his Heart of Darkness, life is as “inscrutable as destiny.”

In that destiny was a managing director of the top oil marketing firm in the sub-continent, senator, governor, party leader, and statesman. When he was a child, according to the story, he visited the Governor’s House in Ibadan with his father who was also a prominent politician. When he sat leisurely, his father told Abiola to sit properly. “Sit like a governor,” he instructed. “One day, you too will become a governor.”

He never forgot that moment in prophetic attitude. But he did not seem the man for politics when he travelled to the United States, excelled in his studies and even worked menial jobs including in a mortuary. He combined studies with work and joys of America, even dating a Miss Buffalo as part of his thrills of youth.

He did not return with any connections or plum jobs waiting in Nigeria. He got his jobs and worked his way up the ladder. As a corporate man, he looked at politics from the distance. He wanted to reach the acme of career before he ventured into the vocations of father and uncle. He stunned his wife when he eventually did. She did not envisage an Abiola, who could sit with artisans, workers and the lower rung of the society. He had been prim at the top for so long. They met at Marina in Lagos when she first shunned him and a proud Ajimobi waited in ambush. So, an Ajimobi, who chummed with market men and women, mechanics, road transport workers, etc, was new to him. “It’s in my blood,” he assured her. He became senator, and after a battle he became a governor, not once, but a jinx breaker by taking it twice.

He understood himself, and applied his energies and vision as governor in Oyo State. He is the most consequential figure in modern Oyo State. He was focused, if sometimes too blunt for his people. But he was authentic and refreshed with his candour. He did not play double standards or suffer fools gladly. He had a portrait of a lion in his sitting room in which the lion says he will not eat grass no matter how hungry he is, not because of pride, but that is who he is. Hence an Ajimobi would berate some errant students who would not listen to a governor. He asked them to obey constituted authority because that was how he was raised, not as a generation of petulant boys who look their elders in the eye with impunity. Or in the Obaship struggle in which he confided to me that the people agreed to his reforms in private only to turncoat in public. He did not chafe under pressure but insisted on the point he had made. That is the measure of courage in leadership.

He had his flaws. But he was more tender than many knew. A childhood friend of his in the United States was walking through Marina with his wife and stopped at National Oil, and said he knew the boss of that company and walked in. He was allowed up to its top floor. The secretary would not let him see the boss. He was impatient and left with a note. Once Ajimobi learned of it, he shut down every door or lift until they found the fellow who had almost left the building. He spent that night in Ajimobi’s home after asking his wife to prepare a meal for an august visitor.

When he was a teen, he accompanied his mother to a village in the southwest where she sold gold. They had an accident in which the vehicle somersaulted. He survived with his mother. But a certain fellow who was walking by, looked at the lad, still bleeding from a wound that become a lifelong scar. “Take care of that boy,” he charged his mother, “he will become somebody big in this land.”

Whatever the status of the man, whether prophet, or whether human or spirit, no one could discount that his tongue lit with fire. The boy, who fell into a ditch in an accident and bore a scar on his head and escaped death with his mother beside him in a rustic retreat in Yoruba land, grew over the years to travel all over the world, to school in some of the world’s tony universities, to grow in fame and fortune, to become a headline grabber in the nation’s television, newspapers and magazines, became a mobiliser of men and resources, became a helmsman in corporate Nigeria, soared to victory as a man of power, held positions of envy as he leapt from rung to rung, was sworn in as a senator of Oyo State and the Federal Republic of Nigeria and, after a grueling epic of a fight both in the courts and on the ballot box, distinguished himself not only as a governor but has set a record as the first personage to mount the seat as governor twice in a historic state of kings and kin, of quicksand loyalties and royalties in the capital, Ibadan, signposted as one of Africa’s largest cities. He bowed out as governor with the garland and sobriquet: Ko sele ri – It has never happened before.