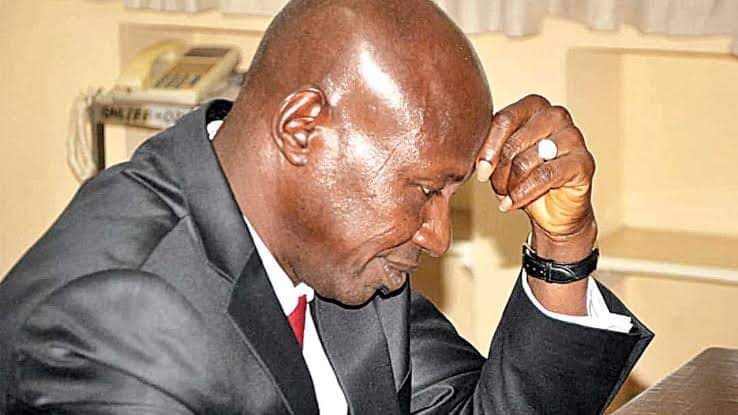

Is the federal government’s war against corruption in Nigeria no longer the causa proxima for the emergence of President Muhammadu Buhari’s regime or what? Or is that Nigerians don’t trust the government in its fight against corruption? Since the news of Magu’s detention, interrogation, and now substitution, at the instigation of the Attorney General of the Federation and Minister of Justice, Abubakar Malami, SAN, broke, I have been watching to see whether some Nigerians or in the least the self-styled anti-corruption groups would rise up to his defence.

Could it be that these groups, really don’t buy into the fight against corruption, or is it that they never trusted Ibrahim Magu, in his avowed determination to wrestle corruption to the ground? How come there are no protests over the sudden clampdown on Magu, as we saw, when President Umaru Musa Yar’Adua, initiated the duplicitous process to force out the first EFCC anti-corruption czar, Nuhu Ribadu, in December 2007?

Of note, a cursory look at the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (Establishment) Act shows that the chairman of the commission has no security of tenure. Section 3(1) of the Act provides: “The chairman and members of the commission other than ex-officio members shall hold office for a period of four years and may be re-appointed for a further term and no more.” The above provision makes for determinable tenure, without security.

By the provision of section 3(2) of the Act: “A member of the commission may at any time be removed by the president for inability to discharge the functions of his office (whether arising from infirmity of mind or body or any other cause) or for misconduct or if the president is satisfied that it is not in the interest of the commission or the interest of the public that the member should continue in office.”

By that provision, it is presumed that the chairman of the commission can be treated like any other member, with respect to cessation of membership of the commission. So, under the EFCC Act, a president can remove the chairman of the commission for a whimsical reason, or for no reason at all, considering the subjective nature of the powers granted the president under the Act.

In Magu’s case, however, the president has opted to exercise his powers after due diligence, following the allegations of misconduct levelled against Magu, by the AGF, Abubakar Malami (SAN). He set up a presidential committee headed by a retired President of the Court of Appeal, Justice Ayo Salami; a man who suffered untold humiliation in the hands of his colleagues, over allegations proven to be spurious.

According to reports, Salami has promised to be fair in the assignment. Without prejudice to the administrative enquiry, some of the allegations against the EFCC chairman are rather tenuous, unless there are underlying factors not in the public domain. One of the allegations is insubordination to the office of the AGF, who wrote the petition, against Magu.

While the powers of the AGF, is enormous under the 1999 constitution, the EFCC Act, in my humble view does not contemplate that the chairman of the commission should take orders from the office of the AGF. Any claim of insubordination, should only be of significance, if the chairman is working at cross purposes with the directive of the president, who is the overall boss of both the EFCC chairman and the AGF.

Considering the clear intendment of the Act, the EFCC is scheduled to be reasonably independent, in the war against economic and financial crimes. So, should an AGF, for instance, engage in a financial crime, the commission should be able to investigate and prosecute such an AGF. Again, without prejudice to the specific act of insubordination complained of, against Magu; the EFCC should be independent enough to investigate any member of the executive, just as it can investigate any member of the legislature or the judiciary.

A comparison of the EFCC Act and the Independent Corrupt Practices & Other Related Offences Commission (ICPC) Act shows that the chairman of the ICPC has a secure tenure, unlike the chairman of the EFCC. Yet, these two commissions are geared to help the country fight the scourge of corruption, and both organisations, were established by President Olusegun Obasanjo’s administration, about the same period. Interestingly, the EFCC has by its action proven to be more proactive in the fight against corruption, more than the ICPC.

Section 3(7) of the ICPC Act, provides that the chairman shall hold office for five years in the first instance, and members apparently for four years in the first instance. On security of tenure, section 3(8) provides: “Notwithstanding the provision of section 3(7) of this Act, the chairman or any member of the commission may at any time be removed from office by the president acting on an address supported by two-thirds majority of the senate praying the he be removed for inability to discharge the functions of his office (whether arising from infirmity of mind or body or any other cause) or for misconduct.”

Magu, like his predecessors, will be booted out, ignominiously, unless a miracle happens. On its part, no ICPC chairman, has been sacked before the expiration of his tenure, as far as I know. Comparing the productivity of the two commissions, many would give thumbs up to the EFCC, as being more proactive in the fight against corruption, within and outside government circles. Again, between the two agencies, the EFCC is more feared. Could that fear be, because they often employ strong-arm tactics, or is it because of their determination to fight corruption?

Perhaps, the lawmakers should consider, whether there is a connection between the hyperactive performances of the chairmen of the EFCC and the more matured disposition of the chairmen of the ICPC, and the security of tenure. Could the hyperactivity be an effort to retain the plum job, or is it the calibre of persons who the respective Acts provides, should be appointed to head the two different commissions. Many who have been maltreated by the EFCC would wish Magu, an immediate repose from the plum position. But there are those making a song and dance of Magu’s predicament, without minding their celebrated immorality.

As the Minister of Information and Culture, Lai Mohammed, would have said, the complaint about the wrongheadedness or even highhandedness in the war against corruption is corruption fighting back. I shudder that there is not a whimper, in defence of Magu, one of the poster boys, of the Buhari’s administration in the past five years. Could there be more than meets the eye, in the unfolding Ibrahim Magu’s saga?