On the surface, the arrest, detention and grilling of former Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) chairman, Ibrahim Magu, should underscore President Muhammadu Buhari’s commitment to the war against corruption and emboldened respect for the rule of law.

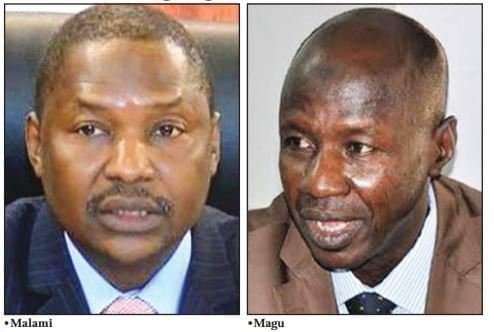

Orchestrated almost wholly by the Justice minister and Attorney General of the Federation (AGF), Abubakar Malami, the detention and grilling of the EFCC boss represent his firmer control of the agencies constitutionally subordinated to his office.

For about four years, Messrs Malami and Magu looked daggers at each other, with the latter reluctant to submit to the former.

The EFCC at its founding had adopted the culture of being independent of the AGF’s office, preferring to be either independent or encouraged by the presidency to be pretentious. The EFCC’s mode of operation is likely to change henceforth, but so its vigorous devil-may-care spirit.

The surface currents observable in the Magu debacle are significantly different from its undertow, a counterforce flowing beneath the surface, speaking more loudly to many years of running the presidency incompetently or confusedly.

Three points illustrate this confusion. First, Mr Magu was clumsily arrested, with no security agency admitting it carried out the act. It is inconceivable that he would be asked to report to the presidency and he would decline.

Instead, he was confronted in the streets and taken straight to be grilled by a panel, detained for days without the opportunity to arm himself with necessary facts to refute or rebut the allegations against him, and kept in isolation days on end.

Worse, it took days for the government to announce an interim successor. Why could he not be replaced immediately through a sack or redeployment letter, and a successor announced in his place?

Was it so complicated for the president to sack an officer he appointed, especially someone whose nomination was not confirmed by the senate?

Contrary to the impression which Mr Magu’s sack was meant to create, his fate did not point at long last to a refinement of the presidency’s mode of operation, but the reinforcement of its unsuccessful battle to restore order and elegance to a modern, 21st century presidency.

It is ironic that Mr Malami and his office, which both suffer credibility issues in administering the country’s laws and safeguarding its criminal justice system, should be the inspiration behind the Magu sack.

If for five years the AGF could not rein in the EFCC, it is not only Mr Malami’s lack of fidelity to the laws of the land that is to blame, but principally the presidency’s dithering and detachment.

The AGF had complained loudly, fought Mr Magu openly, and at the risk of plunging the presidency into chaos joined forces with other shadowy persons in the corridors of power to prosecute his wars against the EFCC.

Mr Malami now has the upper hand, as indeed the constitution has all along envisaged. But whether this will last, especially in the face of his reprehensible and atrocious interpretation and administration of the laws of the land, or whether it is even in the interest of the country that Mr Malami should retain the upper hand given his own track records and the deplorable state of the anti-corruption war, is a different thing altogether.

Secondly, there is yet much worse on the loose, a situation that makes it difficult to absolve the presidency, Mr Malami or Mr Magu.

The EFCC boss is embroiled in some kind of struggle with Mr Malami because neither the presidency nor the AGF nor yet the EFCC has a clue how the anti-corruption war should be prosecuted.

In addition, none of the three bodies has had the discipline to even make it work, especially given the chaotic frontlines of the war.

The problem, however, goes far back in time, indeed to the very beginning when ex-president Olusegun Obasanjo established the commission.

It was necessary to imbue the agency with the right and practicable philosophical foundations, whether in terms of its structure and operational procedures or in terms of its objectives.

Chief Obasanjo was a committed and hardworking leader, but he lacked the philosophical graces to imbue anything to anyone or agency.

Unfortunately too, the EFCC’s first chairman, the young and uppity Nuhu Ribadu, was too impressionable and heady to set the right precedents for the young organisation.

Forced by circumstances to operate without the right philosophic foundation and operational depth, the EFCC has over the years stumbled from one mistake or childish fantasy to another, and between inspiring achievements and depressing failures.

From Mr Ribadu to Mr Magu, the EFCC vacillated between obeying the law one day and disobeying it another day, with both contradictory and sometimes anomalous positions justified on the grounds of patriotism and the need to rid the country of corruption.

Because the commission lacked or repudiated the right philosophy, it was unable to appreciate that subverting the law was even worse than invading the national treasury, with both vices regarded as appalling manifestations of the different faces of corruption.

The EFCC also sometimes involved itself brazenly and without compunction in politics, such as participating in the impeachment — more accurately deposition — of governors and state parliaments, again justifying these on the grounds of saving the country from the grip of thieves.

It was obviously too much to ask the Buhari presidency to appreciate these dangerous underpinnings in the EFCC, not to talk of enunciating wholesale reforms to help build up the anti-graft agency into a reliable and durable institution. Consequently, since 2015, the malady in the EFCC has continued apace, only this time more chaotically.

The AGF has fought the EFCC, just as cabals and powerful interests have sundered the presidency and rendered it a house divided against itself.

Mr Magu, as difficult as he was as the EFCC boss, and as intemperate as many see him, was not the problem with the EFCC.

It is indeed embarrassing that the AGF has seemed to elevate his problem with Mr Magu into a national issue deserving comments and impassioned arguments.

The problem of the agency is structural and systemic, a problem that can absolutely not be divorced from the shambolic nature of the Nigerian presidency.

The conclusion indeed is that though Nigeria operates the American presidential system, almost to the last letter of the US constitution, it lacks the latter’s philosophical and abstract constitutional constructs.

Chief Obasanjo could not inspire the needed change as the first president of the Fourth Republic, and his successors Goodluck Jonathan and President Buhari could also not transcend the mundaneness and soulless reproduction of the Nigerian constitution to birth a great future for the country and its institutions.

Since its founding, the EFCC, through its four chairmen, has operated the same rule book. The next chairman will not and cannot be different.

Thirdly, apart from the systemic problems confronting the combustible troika of EFCC, AGF and presidency, no one has addressed the simple and provocative fact that the anti-corruption war has remained unscientific and pedestrian.

The country mistakes loot recovery for anti-graft war, the scaffolding for the building. Or perhaps Nigerians superimpose their mistaken perceptions on the obnoxious realities of the EFCC.

Nigeria runs an unrealistic and untenable federal structure where mediocrity is rewarded, cultural differences are foolishly abrogated in the name of unity, and states and local governments, not to say agencies, are encouraged to leech on one another, gratify the predatory instincts of their managers and chief executives, and discourage or diminish creativity and initiative.

The country has become one huge pell-mell of discordant and broken ideas, weak institutions and white elephant projects.

Its political structure is also absolutely unworkable; it has become a money-guzzling machine dedicated to the worst forms of idleness, sense of entitlement and hedonism.

The EFCC can do nothing to affect these systemic problems, let alone save itself from the hands of its grandiose and extravagant managers and self-serving Justice Ministry supervisors.

If the country wants to fight corruption, it must first set the right structural foundation. Run a lean, one-chamber national legislature, redraw the states into self-sufficient entities, eliminate virtually all the allowances legislators take, reconstitute the civil service, pay sensible wages, reform the judiciary, merge and rationalise agencies, recompose the police along state lines and put federal checks in place to start with, reform the electoral system, and above all reform the financial system to track cash flows and make transactions on housing and other consumables affordable and feasible.

This calls for nothing short of a revolution. But it is either this revolution is carried out or the country will continue to stumble along in its meaningless anti-graft war and squabbling EFCC and Justice ministry officials.

Given his many countervailing legal interpretations, many of them unsolicited, Mr Malami simply does not have the credibility or depth to inspire anything, not to talk of effecting positive changes in the EFCC; nor did Mr Magu, like his predecessors, have the depth and temper to run the EFCC. Taking sides with one or the other is tilting at windmills.

But perhaps a sublime change is finally afoot in the presidency. The upper hand Mr Malami has just seized viz-a-viz the EFCC may in fact be a reflection of either the re-establishment or imposition of a new order in the presidency.

Previously, a chaotic system of contrapuntal exercise of powers reigned supreme in the presidency, with cabals and anti-cabals carving out impregnable fortresses for themselves and their minions, and open epistolary battles rearing their heads now and again.

Today, the National Security Adviser (NSA) is reasserting himself and his office, and the AGF is also following suit. The presidency has obviously become more decisive, and it will increasingly assert itself in future disputes between appointees.

But that it has become more decisive does not mean it has correspondingly become wise. So far, its understanding of decisiveness is limited to simplistically taken sides with one side in all the disputes it has become involved in.

Faced with petty and contrived crises in the National Working Committee (NWC) of the ruling All Progressives Congress (APC), the presidency simply cut the Gordian knot by siding with the rebels.

Faced with the battle between the NSA and military chiefs, the presidency has seemed to side with the former. And faced with the struggle between the EFCC and the AGF, the presidency has obviously and perhaps heedlessly sided with the latter.

In both the NSA and AGF efforts to reassert themselves, the constitution is of course on their side. But beyond this, it was also necessary for the presidency to appreciate the dynamics of these struggles and to judge whether the officials fighting for dominance possess the moral and administrative qualifications to lead the charges.

More, it was also expected that the presidency would take sides only when their position aligns with its philosophy of governance and perhaps the philosophy of their party and government.

There is no indication that the presidency’s involvement in these struggles have not been generally ordinary and impulsive.

However, there is at least a tangential break with the dreary and dithering past, a demonstration that the presidency now wishes to own its ideas and promptly take decisions.

There must, however, be a corresponding deepening of the intellectual basis by which those decisions are taken.

Last week, the press was inundated by the grounds for suspending, detaining and interrogating Mr Magu. He is unlikely to be guilty of all the allegations levelled against him, not to talk of some other hitherto unknown allegations dredged up by many commentators.

He is also unlikely to be vindicated. The president was at liberty to dispense with the services of the former EFCC boss, but that simple task was not accomplished with the finesse expected of the president’s office.

And until the panel looking into the allegations against Mr Magu turns in its report, it will be unreasonable to give a conclusive opinion of how the obstreperous Mr Magu fared in office: whether he is as altruistic as he gives the impression, or whether he is an empty and sclerotic vessel gracelessly typified by the Nigerian public servant.

The presidency may have become somewhat and clumsily more decisive; it must now find the inspiration and discipline to refine its methods.

Discrediting an official first in the media before giving him the boot, often through unconstitutional means, is reprehensible.

The presidency must never give the impression that sacking an appointee has become so difficult that the government must inflict collateral pain on the public.

They didn’t even need a justification to ease out Mr Magu, so why drag the public through an unseemly rigmarole?

Before the former Chief Justice of Nigeria, Walter Onnoghen, was arbitrarily retired, they also dragged him and the rest of the country through deplorable propaganda and needless judicial controversy, a tactic that was to be replicated in the sacking of former APC chairman, Adams Oshiomhole.

It is unkind to the affected officials and contemptuous of the country. It is even sadder that commentators lined up behind the two camps, the government and its harried appointees.

This is needless. Except the constitution forbids it, and this presidency has not been known to be finicky about the constitution anyway, let it sack its appointees as it deems fit. But it has no incentive to do it in a way that sullies its image.