In early July 1998, I traveled to Nigeria with Undersecretary of State for Political Affairs Tom Pickering, who was then among the most senior career Foreign Service Officers. As assistant secretary of state for African Affairs, I had gotten to know Pickering, my immediate boss, as a wise, fast-talking, and deeply knowledgeable diplomat. Having served as ambassador to six major countries and the United Nations, Pickering had seen and heard almost everything.

The purpose of our trip to Nigeria was to encourage a responsible political transition. The nasty former dictator, Sani Abacha, had died a month earlier in the company of prostitutes. Viagra was reportedly involved. His interim successor was a moderate leader, Abdulsalami Abubakar, who hoped to shepherd Nigeria through a democratic election to select its new leader.

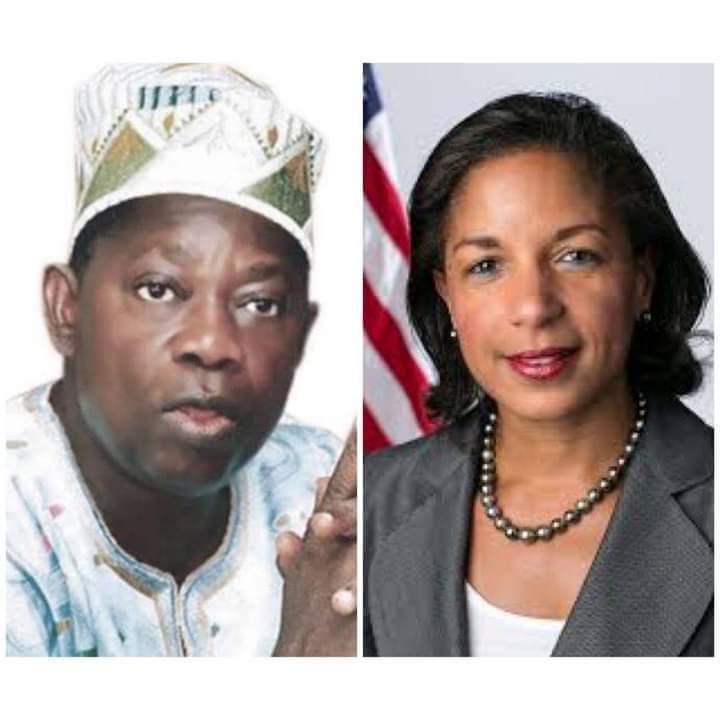

A primary objective of our visit was to meet the wrongfully imprisoned opposition leader, Moshood Abiola. He was the presumed winner of Nigeria’s 1993 election, but the results were annulled, and he was later arrested. We hoped to negotiate his freedom so that he could participate in the upcoming election.

Along with Pickering and U.S ambassador to Nigeria Bill Twadell, I met Mr. Abiola in an austere government guesthouse on the vast presidential complex in the capital, Abuja. A large and imposing man, Abiola came with his minder shortly after we arrived. Pickering, a former ambassador to Nigeria, knew Abiola from years past and greeted him warmly. Abiola, robust and happy to see us, sat on the couch and began to tell us how poorly he had been treated during his four years in prison. He was wearing sandals and multilayered traditional Nigerian dress. I noted that his ankles were swollen.

About five minutes into the conversation, Abiola started to cough, at first mildly and intermittently, and then wrackingly with consistency. He said he was hot, so I asked his dutiful minder, “Please turn up the air-conditioning.” Noticing a tea service on the table between us, I offered Abiola, “Would you like some tea to help calm your cough?”

“Yes,” he said, with appreciation, and I poured him a cup. He sipped it, but continued coughing. Increasingly uncomfortable, Abiola removed his outer layer, leaving one layer on top. I shot Pickering a worried glance.

The coughing became dramatic. I told the assembled men, “I think we better call for a doctor.” No one argued. The minder immediately placed the call. Abiola asked to be excused and went into the bathroom of our meeting room. When he emerged, he was bare-chested and sweating profusely, barely able to talk. He lay down on the couch writhing and then rolled facedown onto the floor. The doctor arrived promptly, took a quick look at him, and declared that Abiola was having a heart attack and must be transported to the hospital immediately. The men labored to lift the heavy Abiola into a small car, and we rushed to the nearby, rudimentary presidential hospital. I grabbed his eye-glasses off of a side table where he left them, his only belonging, thinking of his daughter Hafsat in the U.S whom I’d met before we left. The doctors worked on him, furiously, but within an hour they pronounced him dead.

We braced for violence. Abiola’s sudden and mysterious death would hit like a bombshell in Nigeria’s political tinderbox. Conspiracy theories would spread like metastatic cancer. Serious unrest throughout Nigeria was possible. Washington would hyperventilate, since it’s not every day a major figure drops dead with senior U.S officials. His family would need to be told. And, urgently, Nigeria’s acting president would have to hear directly from us, even though his minister was present at the hospital and knew how it went down.

Ambassador Twadell panicked and urged me and Pickering to rush to the airport and leave the country immediately. “Hell no,” we said. This delicate situation required deft management, not a hurried exit in a cloud of suspicion.

Right away, I called National Security Advisor Sandy Berger, my former boss, briefed him, and dictated a White House press release. Then we went to the Nigerian presidential palace to relay the entire drama to the acting president. We urged him to issue a careful statement to announce the establishment of an autopsy by international experts, in order to quell rife speculation and limit the potential violence. The acting president did both.

Next, Pickering, Twadell, and I went with former Nigerian Foreign Minister Baba Kingibe to see Abiola’s wives and daughters. All of us walked in together, but soon I realized that I was effectively alone in the room with these distraught women. The men had hung far back and left the job to me—just like the pouring of the tea. I proceeded to explain that their husband/father was dead. He had died of an apparent heart attack that began in our meeting. The doctors did all they could to save him but could not. The ladies’ wailing was so intense, it haunts me to this day.

We briefed the press, and I returned to the U.S embassy to write the official cable to report what had happened. As a senior official, I almost never wrote up cables summarizing meetings but in this case there was no more efficient way to ensure we got this very important history straight.

As I was typing, I heard in the distance on the CNN a familiar voice of indignation. It was none other than the Reverend Jesse Jackson, then serving as President Clinton’s special envoy for the promotion of democracy in Africa. Reverend Jackson served capably in this role, and with good intentions, but on this occasion, I could have throttled him. He was riffling about how Abiola died under suspicious circumstances in a meeting with U.S. officials. I could not believe my ears—our own guy implying we were killers! Immediately, I placed a call to his longtime aide Yuri and asked them to shut the Reverend down. “Please, just get him off the set.” That happened, even as I was still watching the segment.

We stayed overnight in Nigeria to try to calm things, offer any needed assistance to the government, and make an orderly departure. Fortunately, despite deep public upset, no significant violence occurred. The autopsy eventually confirmed the cause of death as a heart attack. Nonetheless, it was Nigeria where conspiracy theories abound. The most popular, which still has currency over twenty years later, is that I killed Abiola by pouring him poisoned tea.

From that experience, I found that being a woman policymaker comes with unique hazards. The men would not have offered, much less thought, to pour the tea. They may have swiftly called for a doctor. They may not have been able to break the bad news to the wives. Not for the first time, it was I, not they, who took the public fall for a crime nobody committed.

Susan Rice on her Nigerian connection:

Almost immediately after their wedding, my parents moved to Lagos, Nigeria, where Dad had been sent by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) as a research advisor to help establish the Central Bank of Nigeria in the wake of the country’s independence. Mom took leave from the College Board and worked for the Ford Foundation as an educational specialist for West Africa. Their two years in Nigeria, punctuated by travel around West Africa and Europe, were, by all accounts, enjoyable. They amassed an impressive collection of Nigerian art, including valuable sculptures that were a visual fixture of my upbringing.

I was conceived in Nigeria. Toward the end of their stay, Mom became pregnant with me, and I have long amused myself with the hypothesis that my origins in Nigeria, combined with my Irish and Jamaican ancestors, explain a lot both about my temperament and attraction to all things international.

-Rice former US Ambassador to UN and former US National Security Adviser in her Memoir, TOUGH LOVE: MY STORY OF THINGS WORTH FIGTHING FOR