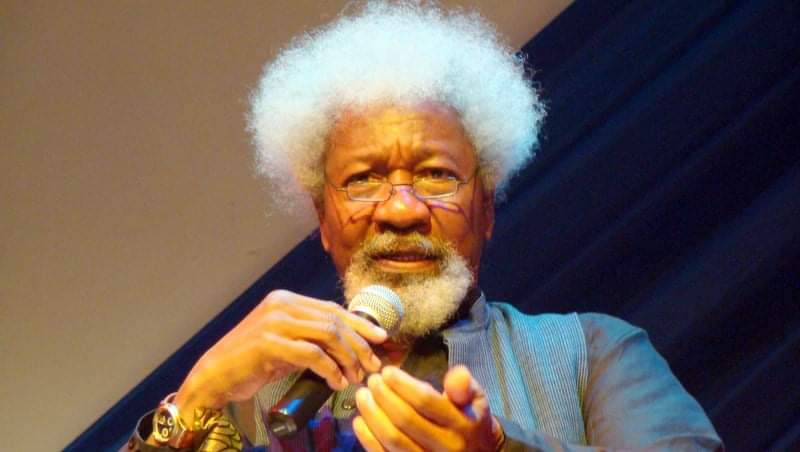

IT is a novel as cornucopia.

For those who have read Professor Wole Soyinka’s new novel, they may not be sure what to call it. That is its enigma. Some may say it is journalism, and for good reason. They meet the benign ghost of the former Oyo State Governor, Abiola Ajimobi. They cannot miss the grinning mien of Rochas Okorocha and his happiness ministry of in-law, siblings and cronies. Also from Kano, Governor Ganduje skewers emirs into sundry emirates.

Of course, we also see Okija, the shrine as cause celebre. The ecclesiastical takes centre court, with a cleric, neither Muslim nor Christian, both though and more ensconced in his charismatic, ecumenical soul of grand deception. He is the sort you saw thumping a fist on teevee, or the imam of reclusive and taciturn awe in the neighbourhood. For good measure, you meet, pop-eyed, the mystic island of Sat Guru Maharaji on the express.

This sort of novel is what French critics call romans a clef, a novel of recognition, a novel with a key. In Primary Colours, novelist Joe Klein tosses President Clinton about.

The novel, Chronicles Of the Happiest People On Earth, Soyinka’s third, is a recycling of the author’s work, parents giving birth to a child, but the child taking on all their traits while individualising them. The child is theirs, but the child is his own person. It is 506-page tome of a society of oddballs and bloodthirsty villains and abbreviated heroes.

If you want satire, you can keel over your chair. For instance, we see a prayer session when the pastor as patriarch, Pa Davina’s “rising obastacle” around his loins confronts a woman on her knees. She genuflects, face before Terigbogo’s mid-section. Terigbogo in Yoruba means “bow your head for glory.” Pa Davina is also named Terigbogo. Or when a governor arrives for an award with an exaggerated caravan and he flicks out a grateful dagger from layers of babanriga. The host faints and finds himself in Dubai overnight. Or Badetona’s encounter with a lizard that ignites a wife’s fear and sees it as an omen of wizardry. The husband, a skeptic, has to ascend a breathtaking mountain for absolution with, of course, the mystic masseur of the soul, Pa Davina.

The novel takes a swipe at religious hypocrisy and sexual peccadillos of men of power and mystery, oaths upend oaths. We see this in the triumphs of the Jero plays and the Lion and the Jewel. We also see the exploits of Madmen and Specialists in one of the main characters, Duyole Pitan-Payne, although it is his son who is the maleficent type of Dr. Bero. That also gives a hint of Death and the King’s Horseman in the strain where son charts a different path from father, in an oedipal betrayal.

The novel is about four main persons, friends, ostensibly since they leave school. In his first novel, The Interpreters, we have five graduates confronting a teething nation. Their idealism falters. In this Chronicles, the four are supposed to belong to a Gong of Four, a fraternity of good intention with a dose of the idealistic. Badetona is a bureaucrat, Pitan-Payne an engineer, Kighare Menka a surgeon, and Farodion. Who is Farodion? He is the mystery man of the tale, a man of many names, many faiths, many countries, many sojourns, a man with a pact with life and death. We do not know him until the story ends, and the sophistication of his treachery enlarges the skewed nature of the happiness project that Nigeria is.

The tragedy re-echoes Soyinka’s lament of a wasted generation, brilliant idealists who make bonfires of a nation’s dream. You cannot also miss the motif of the tyrant in power, the hustlers around him, the vanity of bringing up those who know nothing into reckoning of the wrong kind. Opera Wonyosi is his play of political indulgence, megalomania and glamorous putrescence, where a character says, “he who begs, bags.” A fellow, Ubenzy Oromotayo, is the dispenser of awards that flatter the egos of vain and parasitic elite. Oddballs and lofty maniacs replace the good. A street gang dressed up as models. Opera Wonyosi adapts The Beggar’s Opera, Playwright John Gay’s play that flays the first British Prime Minister Robert Walpole. It also adapts Brecht’s Three Penny opera.

The motif of ritual and body parts undergirds the tale. He calls it the “meat mall.” It weaves the story of kilishi and Boko Haram, and the ritual murder in the south as well as nurses and hospital staff across the country who make a killing out of blood and offal of patients purloined from hospital theatres. The high and mighty use albinos and other human parts for wealth and power. It is all tied together in the Okija tale, where we see him soar into the roman a clef territory again. The novel tells, with a sardonic eye, the familiar tales of a governor abducted, a toilet farce, a police officer’s list of marque members and a national audience in bewilderment.

The cadaverous mess is the undertow of a society that claps over a crowd of mourners, a carapace above dead men’s bones, where pious ecstasy props the lies of priests and political leaders. It creeps into family. The Pitan-Payne clan is a connected, well-known name. But the fellow is not loved. They crave his wealth. His son colludes with his enemies to destroy him because, somehow, the son envies his father’s prowess.

The novel gets personal with Pitan-Payne in a recast of Femi Johnson, the bosom friend of the bard. In his memoirs, You Must set Forth At Dawn, he recounts his effort to exhume his friend’s remains and rebury him here at home.

In the novel, he makes the yarn a series of genres. A comedy, when the deceased’s sister pours accolades on Austria’s scenic beauty and lashes at Nigeria’s slovenly environment, whereas she fattened on defacing the Marina in Lagos. A thriller in the tale of outsmarting the family obstruction in bringing the body home. A whodunit in the inquiry into the fiction that Menka hid something inside his friend’s body. And, of course, his son’s role in his father’s death. A farce in the dance march to the funeral. He also gives us a slave trade tapestry as Pitan-Payne, who hails from Badagry, a slave port, has to be returned home to reverse the servile relationship with the west in that symbolic act.

In his interview with The News editor Kunle Ajibade, Soyinka says he is wary of claiming to know the life of any person. And this is wise. No one can appropriate anybody’s interiority. French Philosopher Rousseau asserted that autobiographies are inevitably self-serving. We only cut slices and spices of other’s lives. It is a matter of perspective as Pa Davina himself says in the novel on the issue of happiness.

The happiness of Nigerians is the illusion of wellbeing, a people diagrammed to accept anomie as peace, a sense of life as glee. We are like Sisyphus, who takes the rock up the hill on end. Albert Camus says Sisyphus is happy in his book of essays, The Myth of Sisyphus. Nigerians embrace their joy in rigged elections, in fuel prices that rise, in kidnaps and slit throats, in baby factories. It is what Fela calls Suffering and Smiling.

It is an offering that has it all. Sometimes Soyinka writes with the rigour of an essayist. Sometimes we see the stage as the dramatist unfurls his yarn. Or even as a poet and he gets cryptic. Sometimes he flows as master story teller.

The humour lifts the heavy passages at times, like an engine that revs a B-2 bomber to fly light in the sky. The humour sometimes forgives the prose. But it is no easy read like Things fall Apart or Half of a Yellow Sun. It offers pleasure to those ready to plumb its depths.

Fifty claps for Kabiyesi

HE ascended the throne at 32. Fifty years on, Oba Lamidi Adeyemi III, the Alafin of Oyo, still acquits himself with poise, charisma and a royal presence unsurpassed in the land.

He is the sort of royal who brings compassion and modernity to an institution some have passed off as history. As they say, the king makes the crown.

He has been a crown to the king as well by the majesty of engagement in society these five decades.

He exudes erudition and has positioned himself on the side of the progressive principle of the age.